Irruptions

Where Movements Go to Die

An Analysis of Middle-Class Counterinsurgency in Lincoln, Nebraska

What Is Middle-Class Activism?

Night One: Autonomous Action in Lincoln, Nebraska

Nights Two and Three: Passivity Takes the Reins

Analysis of Nights Two and Three

Night Four: The Activists Protect the Police

Beyond Night Four: The Movement Defeated

Analysis of Night Five and After

Content Warning: This essay focuses on a social justice movement and therefore discusses police violence against black people, sexual assault, and self-defense against the police in the context of protests.

Part 1

This essay is part one of two pieces Irruptions will be releasing regarding the Fall 2021 anti-FIJI protests in Lincoln, Nebraska. This is a continuation of our work from the Summer of 2020, in which we examined the correlation between the arrival of activist leadership onto protest scenes and the subsequent dissipation of political energy within those protests. This pattern has now repeated itself on UNL’s campus in the wake of what appears to be another successfully defeated movement. Emphasizing the importance of study for those engaged in political action, we aim to offer a lens by which to understand this cycle of defeat in which people in Lincoln are trapped.

Here in Part One, we record the trajectory of the anti-FIJI protests that occurred in Lincoln and draw a few conclusions with the goal of challenging the hegemony of middle-class activism in this city. In Part Two, we will further develop aspects of the following analysis to explore the interactions of class, race, and gender within the crowds throughout the protests. Importantly, some vital events are being elided in Part One because they require deeper analysis in Part Two.

Across both parts, we aim to demonstrate the following theses:

-

Many people in Lincoln wish to do more than submit themselves to institutional reformism in response to violence, but they are always already countered by an entrenched counterinsurgency in the form of a clique of middle-class activists.

-

Lincoln’s middle-class activists alienate more militant elements from protests by cultivating atmospheres of suspicion and distrust, thereby discouraging direct action.

-

Speech-giving, petitioning, scheduling meetings with people in power, and “calling your friends out” (these being the endlessly recycled tactics deployed by the middle-class activist clique) ultimately alienate protest attendees and are the primary reason for the chronic dwindling of every movement in Lincoln.

-

The various police agencies in Lincoln rely on middle-class activism as part of their highly effective “get scarce” approach to counterinsurgency.

What follows is a synthesis of, on the one hand, a timeline of events that occurred in Lincoln and, on the other, our analysis of the forces at play in line with the above theses. But first, we must clarify one of our terms.

What Is Middle-Class Activism?

What we lay out in this section considers events through a primarily class-based lens, though the broader analysis will also consider the operations of other identity categories in the dynamics of the anti-FIJI protests (particularly in Part Two). We adopt this class-based lens because we believe that class allegiances and property relations are a primary force at play in the disarticulation of movements in Lincoln.

For the purpose of this essay, we define middle-class activism as follows: A political disposition which emphasizes institutional power as the exclusive means by which to create social change. Middle-class activism can be wielded by people from a variety of social backgrounds, including working-class ones. A person participates in middle-class activism when their attitudes and strategies regarding social change reflect a petty bourgeois class interest.

Middle-class activism protects the interests and property of the powerful. This effect derives from its core assumptions: 1) that corporate and state institutions are capable of rendering “justice” if the oppressed can obtain a voice in the halls of power, and 2) that any direct attacks on corporate and state institutions will make these entities less likely to listen to the demands of the oppressed or admit them into positions of power. At its core, therefore, the logic of middle-class activism rests on the hope that the oppressed can gain entry into the system as it currently exists. Of course, middle-class activists tend to think they are the best candidates for this elevation to power. Therefore, they defend the existing property relations from which they hope to benefit.

These assumptions come into conflict with the historied proletarian impulse toward property destruction. Those who have no hope of and/or do not aspire to join the mythical, propertied middle-class feel no qualms about breaking a window or two if it strikes enough fear in the hearts of landowners to improve the conditions of life. Because many people (whatever their class position) understand that oppression itself is rooted in the present social conditions, they do not see these conditions as aspirations to be guarded, but rather as the very vehicles of their oppression.

This contradiction between middle-class activism and proletarian liberation continually arises within social movements both in Lincoln and abroad.

Night One: Autonomous Action in Lincoln, Nebraska

On Tuesday, August 24th, the University of Nebraska—Lincoln (UNL) was entering its second day of classes. Throughout the day, allegations spread that a female undergraduate student had been violently raped the night before at the Phi Gamma Delta (colloquially known as “FIJI”) fraternity house on campus. FIJI was already considered by students to be a bastion of rapists among the Greek houses. A brief history of FIJI includes more than fourteen allegations of rape on the property since 2017, repeated suspensions and probations by the university, and a vocal right-wing political orientation.

Within hours of the allegations spreading among undergraduate students, calls were circulating within local social media ecosystems for both the alleged rapist and the house itself to be expelled from UNL.

On the same night as the allegations had proliferated, a demonstration was called outside the fraternity house. No clear leaders emerged in the run-up to the protest, and, as the night set, a crowd of approximately one thousand assembled. image

At first, the protest was highly decentralized and autonomous. The crowd positioned itself directly in front of the FIJI house, with those leading chants rotating in and out from the front. Whoever was leading chants at a given point stood on a stout wall that bordered the fraternity’s lawn, in close proximity to the line of half a dozen UNL police guarding the fraternity house just beyond the wall.

Objects were thrown at the house, and the police perimeter was violated. These actions were met with mixed responses from the crowd, divided between encouragement and remonstrations to “be peaceful.” When the perimeter of the lawn was breached by a protestor, they were ejected from the area by police, but not arrested.

At some point, a megaphone appeared. This changed the tenor of the demonstration, immediately drawing the focus of the crowd to individual speakers on the wall. Convergent with this development, a prominent Lincoln activist who leads the Black Leaders Movement (hereafter referred to as BLM, not to be confused with “Black Lives Matter”) arrived and became the primary possessor of the megaphone. This particular activist appeared repeatedly as a counterinsurgent force last year and has been previously mentioned in our analyses of the George Floyd Rebellion and its subsequent disarticulation. Immediately upon the arrival of this BLM activist, the autonomy of the crowd became overshadowed by peace-policing as the megaphone began to dictate the necessity of a “peaceful protest.”

Analysis of Night One

Just as the George Floyd Rebellion revealed, the unfolding of the first night of anti-FIJI protests demonstrates that, when people feel empowered to respond to structural violence in their communities, they do so. The inclination of many in the crowd on August 24th was to attack the house. They expressed this by lobbing projectiles toward the structure where the alleged rapist had been harbored. Moreover, they demonstrated courage in the face of police repression, openly defying the cops’ attempts to keep them off the lawn. At this point, the crowd was testing the waters, building their courage, seeing how far they could push things. What would they have accomplished if they had been allowed to continue along this course?

An approximate answer may have played out in nearby Iowa City, where, on August 31st, thousands got into the streets to protest an alleged rape at another FIJI fraternity on the University of Iowa campus. The FIJI house was graffitied with prominent tags of “RAPISTS” on the front of the house. Windows were shattered, and several cars were overturned and damaged by the crowd. Additionally, it is our understanding that an entrance to the house was breached by individuals and the interior was damaged.

The difference between Lincoln and Iowa City is that the apparatuses of liberal, middle-class activism were slower to activate in the latter city. This tells us that middle-class activism here in Lincoln is always at the ready to quell unrest. As such, the forces of middle-class activism are the frontline of counterinsurgency, which people must find ways to preemptively circumvent if they wish to exercise their autonomy.

As a postscript to this section, we will mention that a struggle over the megaphone occurred between the activists and a black man from the crowd, which concluded with the man being arrested by the police to the cheers of the activists. We find this incident to be highly disturbing as well as indicative of the relationship between middle-class activism and the police. We will explore this relationship more fully in Part Two.

Nights Two and Three: Passivity Takes the Reins

Going into the second night of protests (Wednesday, August 25th), the middle-class activists had solidified their control. The process resembled the well-oiled machine that was witnessed during the previous summer: a demonstration was called; a peaceful, police-escorted march of pre-determined chants on silent, traffic-free campus streets ensued; more chants were performed outside the fraternity house; and roughly two hours of aimless speaking by the self-proclaimed “revolutionary” BLM activist were delivered through the megaphone.

Unapproved displays of frustration, even those as simple as chucking a water bottle towards the FIJI house, were now met with the swift movement of police towards the point of origin and immediate disapproval from the activists who demanded “respect for the survivor"—according to their definition of "respectful behavior,” of course.

Testimony became the primary mode of protest at this point. Survivors (pre-selected by the activists) stepped up to recount their traumas for the crowd and demand that something be done by university administration. During intermissions in the speeches, the activist-leaders would address the crowd (who had just born witness to some of the worst violences inflicted upon their peers), and tell people that the solutions were petitions, emails, and adding one another on Snapchat to build the movement.

More of the same (though without even so much as a police-escorted march this time) followed on the third night (Thursday, August 26th).

Analysis of Nights Two and Three

Truly, we were shocked by the rapidity with which the middle-class activists stifled the anti-FIJI uprising. The past year and a half had been practice. Every time a movement popped up, middle-class activists—most prolifically the aforementioned BLM founder—would show up and take control. The assumption of control by any member of the middle-class activist clique was inevitably accompanied by the reign of megaphones and police escorts. Wherever they appeared, protestors were told to look out for “outside agitators” and “clout-chasers,” so that suspicious eyes were suddenly upon anyone who looked as though they were about to do anything at all.

The pestilential atmosphere enforced by these activists negated any potential for camaraderie within the crowd. Like cult leaders, the activists positioned themselves as the only ones you can trust, the only ones who are looking out for you, warning the crowd to beware the evil “agitators” who “want to lead you astray.”

The equivocation between, on the one hand, attempts by the crowd to damage the alleged rapist’s property and, on the other, disrespect to the person who was violated at this same property underscores that these activists are coercing crowds into institutional reform as the be-all, end-all. Not even the hackneyed "diversity of tactics” compromise (which operates mostly as an excuse for those who do not want to risk anything to avoid doing so) can be reached when the activists unilaterally ensnare any potential action in these institutional binds.

We propose that, in these so-called safe spaces of civility and high-roadism, where people’s traumas are trotted out like a list of dangers from which the activists “are here to save you,” many felt alienated, disengaged, and alone. Many felt crushed by the weight of the violence of this world and the seeming impossibility of doing anything more than petitioning the powerful to please stop.

Perhaps, this is a better explanation for why these protests repeatedly fizzle out and die. This opposed to the tired script produced by the activists that “people just aren’t committed enough.”

Night Four: The Activists Protect the Police

Night four (Friday, August 27th) was marked by more pacified liberal “action,” now on the steps of the Student Union and away from the fraternity. The crowd had dwindled. The old pattern was strictly maintained: There were calls for officials to be held accountable, organized speeches, calls for petition-signing, and no action by the crowd allowed other than the repititious chants doled out by the activists.

Toward the end of the night, on O Street (a major street near UNL’s campus), Lincoln Police performed a traffic stop on a black man for allegedly violating a traffic signal. As the stop unfolded, he was tazed by the police. A crowd of passersby formed, and the nearby UNL protestors were alerted to the tazing. Not long after the UNL protestors arrived, people were in the streets, blocking cop cars from leaving and bringing their anger to bear against the police. Eventually, the police retreated in the face of the crowd’s anger, at which point the middle-class activists ordered everyone back onto the sidewalk with their megaphone and, eventually, made everyone go home.

Analysis of Night Four

This is another incident which we must elide in Part One so that we can attend to it more fully in Part Two. For now, let it be said that this eruption was the revival of spontaneous crowd solidarity, which, as will be shown below, was swiftly tamped down. Keep an eye on our blog for the more detailed analysis of this incident in Part Two.

Beyond Night Four: The Movement Defeated

Following the confrontation with police on O Street, the activists barely acknowledged the event. The activists, instead, resumed calling for the same type of actions as before, i.e., inaction. The crowd dwindled each subsequent night.

On Sunday, August 29th, news broke that a separate UNL fraternity, Sigma Chi, was placing itself on suspension for a rape that was reported internally. Regardless, the demonstration of Monday, August 30th, was the smallest yet, numbering barely one hundred. The protesters no longer gathered in front of the FIJI house. They were, instead, moved to the other side of the Student Union, entirely out of sight of the fraternity. The demonstration consisted of a candlelight vigil, with more speeches from activists and survivors, followed by a silent march on the traffic-less streets of the campus. The frustration and fatigue of many protestors was palpable, even during the silent march, and several groups did not bother to return to the Union. It should be noted that several of the speech-givers and activists also did not participate in the march, but instead waited at the Union, prepared with their megaphone to funnel the crowd back into repeating the same-old set of chants when they returned.

On Monday, August 30th, only a small handful of protesters arrived at the Student Union, and the low turnout motivated the activists to move the event to a discussion on Zoom, the goals and details of which remain unclear.

On the afternoon of Tuesday, September 1st, the BLM activist who had assumed leadership of the protests posted on Facebook that all scheduled demonstrations were cancelled for the following two weeks (whether protests will resume remains to be seen). The justification given was that the organizers needed to regroup and perform self-care. This has so far been the end of anti-FIJI action in Lincoln. Although some parties attempted to resuscitate the movement following September 1st (using the same top-down, institution-oriented tactics), no significant actions have taken place since that date.

Also on September 1st, a letter surfaced on several social media pages, first appearing (from what we can tell) in a Facebook group for anti-FIJI organizing in Iowa City. This letter purported to be penned by survivors who denounced the cooptation of the Lincoln protests and the silencing of their anger. Although many on the Internet both in Lincoln and Iowa City expressed agreement with the letter’s sentiments, and another middle-class activist (who, previously, had labelled those who attempted to attack the FIJI house “reactionaries”) posted on Facebook an attempt at reflection in their role in stifling the movement, nothing more came of this letter.

Analysis of Night Five and After

The suppression by activists of the anti-police actions of August 27th emphasizes the questionable separation of police from the discussion of sexual violence that occurred on UNL’s campus. Moreover, it is especially confusing considering that the BLM activist who coopted the anti-FIJI movement began their career by imposing themself upon the local expression of the George Floyd Rebellion. Yet, this activist did not once, to our knowledge, mention the countless untested rape kits in police departments around the country. Neither did they draw the clear connection to the staggering rates of rape committed by police officers. No, they were more than happy to have the cops roaming with impunity through a crowd of young women, with no consideration for the fact that, as the protests thinned, the cops would have increasing opportunities to corner these people alone. Women are far from defenseless, but have we not seen what depravity the police are capable of one million times over?

Additionally, it bears mentioning that, despite another rape occurring on UNL’s campus within the same week—an incident that would have instigated full-on rioting in many places—we saw a continued diminishment of protest attendance in Lincoln. Although the middle-class activists continually whine that people are not committed enough to “doing the work,” we think this series of events paints a stark picture of how they are the very problem. Every protest they come to swiftly dies. The fact that they could not mobilize people around a second alleged rape shows, even by their own metrics, that they are not capable of anything other than destroying movements. These activists are the heart of counterinsurgency in Lincoln.

Lastly, we turn our eye to the letter from survivors. Its appearance at the end of the campus’s protests should be taken as a clear diagnosis: Middle-class activism is not the Great Advocate of the Oppressed. Rather, it functions to funnel and silence people’s anger and to annihilate people’s autonomy. Middle-class activism not only implements hierarchical domination of professional activists over lay protestors, and not only does this imposition drive people away in the literal hundreds, but it leaves survivors of sexual assault and other marginalized people more vulnerable to violence because the activists have assured everybody that they are “taking care of it” in the halls of power, where nothing ever changes. Meanwhile, rapists prowl from dozens of fraternities and hundreds of dorm rooms and in every police department. The people who care, the people who are desperate for something, anything, to be done, those who keep coming to the activists because the activists have driven everybody else away—these people walk home from these protests, alone and disempowered, with predators all around them.

People could have built something. But, instead, they were told to sign a petition and go home.

Conclusion

We think the conclusion is clear: Middle-class activism cannot be abided. Any well-meaning liberal in Lincoln and abroad needs to think seriously about what it means to tell people that, when they are attacked, they cannot attack back; that their hurt and anger must be expressed through institutional channels only. Middle-class activism asks that people simply get used to dying while the speech-givers and the influencers jot down on their resumés that they did something, though it is never clear what.

We echo the letter that we published prior to this piece: Go around the forces of middle-class activism. When your autonomy is denied you, experiment with ways to enact it. You do not have to listen to megaphones. You do not have to listen when people tell you your reactions are wrong. The only thing that each of us must do is better equip ourselves to protect one another.

Part 2

All that’s left is this strange, middling part of the population, the curious and powerless aggregate of those who take no sides: the petty bourgeoisie. They have always pretended to believe that the economy is a reality–because their neutrality is safe there. Small business owners, small bosses, minor bureaucrats, professors, journalists, middlemen of every sort make up this non-class…this social gelatin composed of the mass of all those who just want to live their little private lives at a distance from history and its tumults.

–The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection, 33

In this essay, we aim to analyze the protests that occurred between August 24th and 30th, 2021, in so-called Lincoln, Nebraska, in order to elucidate the specific effects of Lincoln-based counterinsurgency tactics in weakening working-class power and solidarity across class lines. Although this piece focuses on geopolitically specific events, we hope it contains valuable analysis for understanding future eruptions of struggle globally.

What we witnessed in Lincoln was the fleeting convergence of the interests of white, petty bourgeois university students engaged in self-defense against rapists with the interests of black proletarians defending themselves against the police, a convergence resembling the organic solidarities established during the George Floyd Rebellion in May and June of 2020. Similarly to the Rebellion, these solidarities were stamped out.

In pursuit of further analyzing this trend, our intent across Parts One and Two of this analysis is to demonstrate the following theses:

-

Many people in Lincoln wish to do more than submit themselves to institutional reformism in response to violence, but they are always already countered by an entrenched counterinsurgency in the form of a clique of middle-class activists.

-

Lincoln’s middle-class activists alienate more militant elements from protests by cultivating atmospheres of suspicion and distrust, thereby discouraging direct action.

-

Speech-giving, petitioning, scheduling meetings with people in power, and “calling your friends out” (these being the endlessly recycled tactics deployed by the middle-class activist clique) ultimately alienate protest attendees and are the primary reason for the chronic dwindling of every movement in Lincoln.

-

The various police agencies in Lincoln rely on middle-class activism as part of their highly effective “get scarce” approach to counterinsurgency.

In Part One, we defined middle-class activism as "a political disposition which emphasizes institutional power as the exclusive means by which to create social change,“ drawing attention to how this activism can be deployed by individuals from various backgrounds and across class lines, so long as the attitudes and strategies towards social change reflect petty bourgeois interests.

Because we are performing a material analysis, we must narrate and critique the actions of specific people. However, being as the object of our critique is a middle-class political orientation rather than any specific individual, we do not use names in either essay and we redact usernames from images below. We wish to be clear that our aim is to critique a set of tactics with clear detrimental effects on Lincoln movements, not to start an online brigade. To ascribe the problems in Lincoln protests to any one person would leave room for new people to deploy the same tactics in the future. We hope, instead, that everyone (including the local activists) can begin thinking about and studying power and protest more from a new standpoint and thereby become more effective in their struggles for liberation.

In this essay, we will expand upon specific events that happened within the short-lived anti-FIJI movement in Lincoln, which we covered at a high level in the previous part. For a higher-view summary and analysis of events between August 24th and August 30th, please refer to Part One.

The Struggle for the Megaphone

The crowd of the first night (August 24th) included a wide array of people who congregated with no unified ideological line besides the common refusal to tolerate sexual violence any longer. However, it must be noted that the protest’s proximity to the university skewed the demographics toward a predominantly white, petty bourgeois inflection. Significantly, a large portion of the crowd was associated with "Greek life” (i.e., fraternity/sorority members and the social spheres surrounding these institutions). We propose that these latter factors made the crowd more likely to identify with institutional power structures than the more proletarian crowds that assembled during the George Floyd Rebellion.

Despite the seemingly counterinsurgent predisposition of the crowd, fury was the primary emotion, and the protest outside FIJI was highly decentralized and autonomous. As we noted in Part One:

Objects were thrown at the house, and the police perimeter was violated. These actions were met with mixed responses from the crowd, divided between encouragement and remonstrations to “be peaceful.” When the perimeter of the lawn was breached by a protestor, they were ejected from the area by police, but not arrested.

When middle-class activists arrived on the scene, a battle of wills emerged between the activists and more “unruly” elements of the crowd. A stream from that night picked up comments from crowd members questioning the activists’ right to take control and commenting that “this isn’t about you,” referring specifically to the prominent Black Leaders’ Movement (BLM) activist discussed in Part One, who had assumed leadership.[1]

We wish, here, to consider a specific incident within this takeover period: As this first protest stretched into the night, a black man took the megaphone from the BLM activist’s hands. The crowd did not like what this man had to say, and he was overwhelmingly booed. There was good reason to shout down the misogynistic comments he made, but the trajectory of this conflict reveals a highly disturbing theme within the activist-led anti-FIJI protests.

As the well-deserved booing continued, the BLM activist attempted to grab the megaphone back from the man. A struggle ensued, during which the man was pushed off the wall and onto the lawn. The police immediately took custody of him and marched him around the corner of the house. The activists then began to cheer at the detainment of this black man by police, and the crowd largely joined. After the cops detained the man, they escorted the megaphone back to the BLM activist, directly handing the item to them. Newly coronated by the police themselves, these leaders—which included the BLM activist and several sorority members—thanked the officers for their intervention and more cheering ensued.

We find this a curious course of action for a so-called abolitionist. The aforementioned BLM activist got their start by coopting the Lincoln expression of the George Floyd Rebellion, yet here they unreservedly allow a black man to be detained by campus police. No effort by any of the activist-leaders was made to stop the police or even to say, “We do not want this man to spew his misogyny, but we also do not want to hand over a black man to cops.” Rather, the easy relationship between activists and police revealed itself. A deal with the devil, the police protect the activists’ privileged position at the head of protests, and the activists stifle any opportunities for direct action.

From all this, we observe that, while there were militant elements in the crowd the first night, the petty bourgeois tendency of the crowd made it easy for a counterinsurgent voice to orient the crowd toward middle-class leaders and their “legitimate” institutions, thereby defeating the possibility of direct conflict. As theorists Shemon and Arturo note in “The Return of John Brown,” “there is nothing more dangerous to the class struggle in the US than the treachery of the white proletariat, which, over the course of its history, has forged an alliance with capital and the state,” and we insist that this is twice as true for the petty bourgeois, white members of the anti-FIJI movement who foreswore their anger in favor of being led into the institutional black hole.

Middle-class activism is a tool that was deployed most recently in the wake of the George Floyd Rebellion to restrain petty bourgeois and white demographics from betraying their race and class positions. And this activism legitimates itself under the guise of “effective action.” In the BLM activist’s own words (from Facebook):

I did not start nor organize that protest, but I did start to lead the people toward the end. It was other women around me who used my mega phone to tell the crowd that we will be back everyday at 10pm until FIJI is blacklisted and banned from campus- to which I offered to organize this protest so that we can actually have direct action that is impactful and not unorganized and erratic.

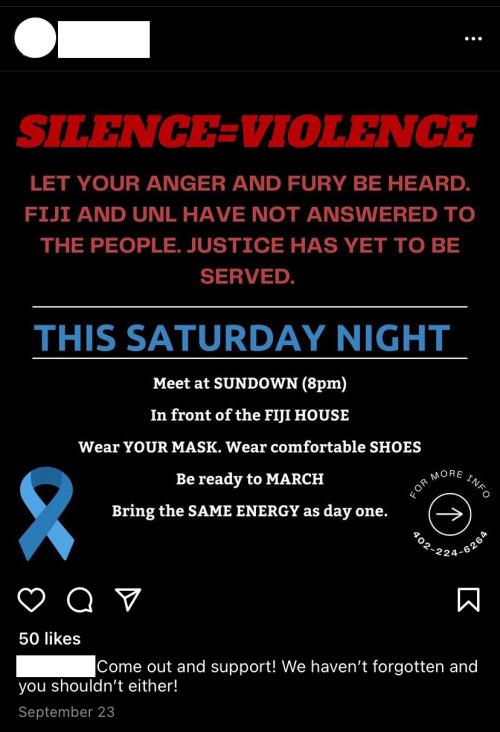

This claim upon “direct action that is impactful” does not reflect the course of events under this activist’s leadership. FIJI was neither blacklisted nor banned from campus, merely temporarily suspended. On September 23rd (over three weeks after the final protest), a post emerged on an anti-sexual assault organizing page on Instagram stating that:

FIJI AND UNL HAVE NOT ANSWERED TO THE PEOPLE. JUSTICE HAS YET TO BE SERVED.

Thus, it seems that the exact opposite of impactful action occurred, and yet the activists continue to call for the same defeated form of “peaceful protest.” And they continue to do so under the direct supervision of police. This begs the question of what movement these activists are actually building, and whose interests their organizing ultimately benefits. To be clear, we make no claim on the intentions of the activists, as we cannot know that. We look, instead, to the effects of their leadership. Based on these outcomes, can we say that the movement for universal emancipation from violence was served? Or was it the movement to subject people to quiet institutional reformism in the face of the many violences of this culture?

Escaping the Enclosure

We transition, now, to a second incident (related to the first) which further reveals the antagonistic position of middle-class activism towards a diversity of tactics in protests.

Toward the end of Night Four (August 27th), on O Street—a major street near the University of Nebraska—Lincoln’s (UNL’s) campus—Lincoln Police performed a traffic stop on a black man for allegedly violating a traffic signal. At the time of the stop, the man’s family and young children were in the vehicle. In the course of the stop, the police attempted to remove the man from his vehicle and a struggle ensued. The police assaulted and tazed the man.

As this was happening, passersby began to shout at the police for their assault on the man. Members of the nearby anti-FIJI protest at UNL were not aware of this altercation at this point. A crowd gathered, and they immediately began chanting, “No Justice, No Peace.” It is notable that the majority of people who initially chose to yell at the cops were working-class black people. Subsequently, word of the police assault soon reached the demonstration a few blocks north. The anti-FIJI demonstrators began marching toward the traffic stop on O Street.

Upon the arrival of these reinforcements (numbering a couple hundred), the police immediately attempted to leave the scene. As the six cruisers present at the stop began to evacuate, several working-class black women ran into the street to block the cruisers and called on everyone else to join them. Several cops then attempted to create a perimeter around the vehicles. The crowd would not let them, however, and surrounded the cars as they attempted to retreat to the west. Amid the flurry of anger, the activists lost control of the crowd’s actions.

This confluence of the traffic stop on O Street with the anti-FIJI protest made possible a spontaneous eruption of activity—the first unplanned and unmanaged moment since the beginning of the protests. The crowd autonomously moved towards the site of police violence and made the decision to get into the street, directly confronting the polices’ abuse of force and helping to physically block their vehicles from leaving the scene. This action represented a critical moment of shared struggle: the predominantly white, petty bourgeois crowd fighting sexual assault on UNL’s campus identified the abuse of power by police and fought back in solidarity with the predominantly working-class black folks that first took the streets to confront the abuse.

Police reinforcements soon arrived and tried to form a loose riot line around a cruiser that had been surrounded by the crowd. They were extremely fearful in the face of a crowd unfazed by officers’ commands to move back. People began penetrating the riot line, and, when cops pushed people, some placed their hands on the cops to fight back. A young black woman was assaulted by an officer and thrown out of the path of the cruiser. This surrounded cruiser eventually found a path out of the crowd and escaped. When this happened, much of the crowd ran to confront a set of other cop cars parked down the street. Several projectiles were thrown at the cars by the crowd.

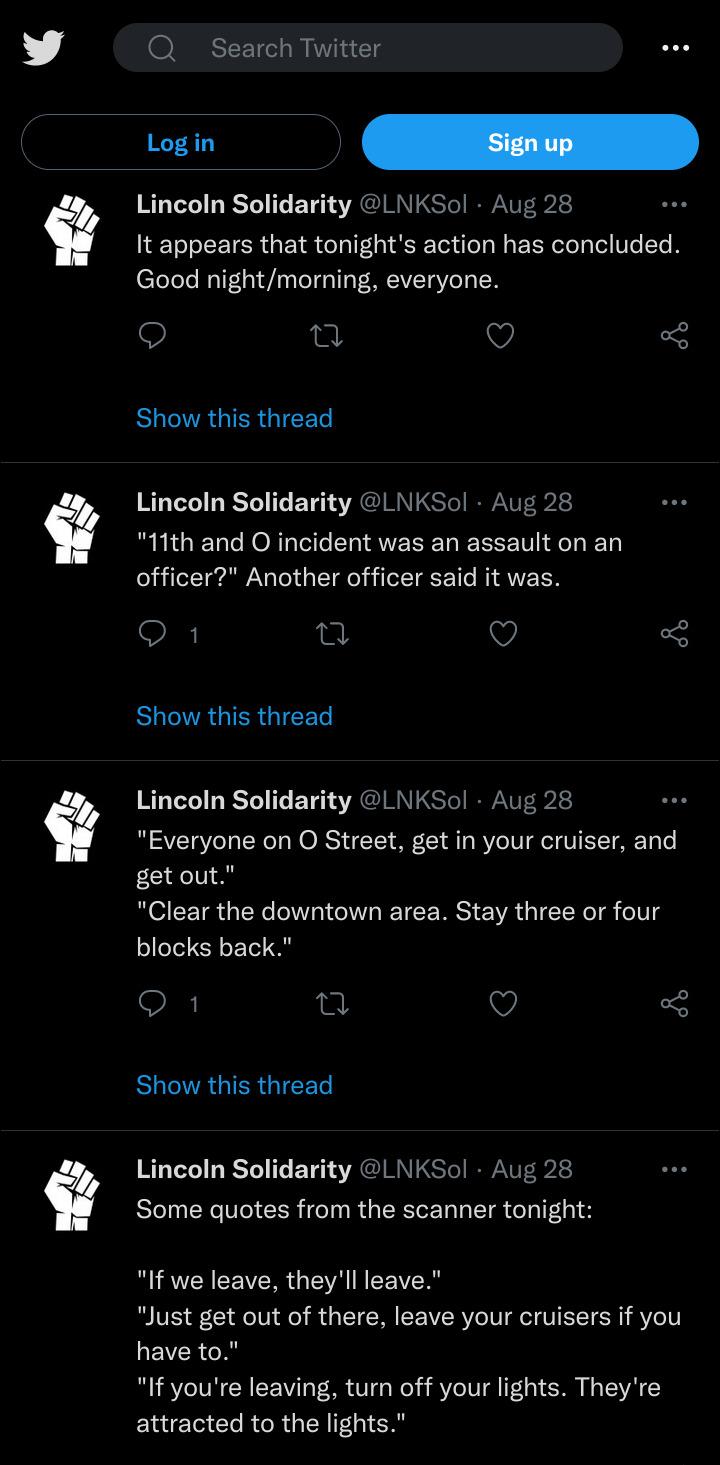

According to the Twitter feed of the local bail fund, police were heard on the scanner during this period saying the following:

-

“If we leave, they’ll leave.”

-

“Just get out of there, leave your cruisers if you have to.”

-

“If you’re leaving, turn off your lights. They’re attracted to the lights.”

-

“Everyone on O Street, get in your cruiser and get out.”

-

“Clear the downtown area. Stay three or four blocks back.”

This chatter reveals what we call LPD’s “get scarce” approach to counterinsurgency. Their primary tactic is to avoid giving protestors a force against which to assemble themselves. This tactic, like with the defeat of the summer’s rebellion, again proved effective in concert with the presence of middle-class activists. After forcing the cops into retreat, many protestors stayed in the street, overwhelmed by what had happened. At this point, several activists, including the BLM activist who had taken control of the protest during the first night, ordered the crowd onto the sidewalk. Shouts of dissent rang out from the crowd (largely from working-class black folks unaffiliated with the anti-FIJI demonstrations). In contrast, the white, petty bourgeois college students from the anti-FIJI demonstration (who now made up most of the crowd) followed the activists’ commands.

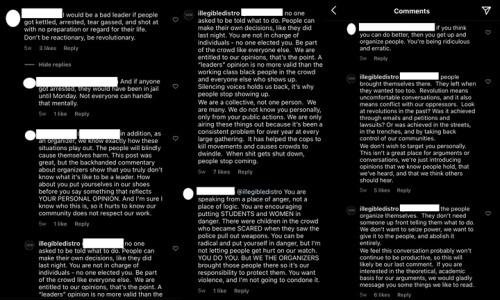

The tactical position in the street was abandoned. Later, in defense of this choice, the BLM activist defended themself on social media:

I would be a bad leader if people got kettled, arrested, tear gassed, and shot at with no preparation or regard for their life.

And if anyone got arrested, they would have been in jail until Monday. Not everyone can handle that mentally.

in addition, as an organizer, we know exactly how these situations play out. The people will blindly cause themselves harm.

As a rebuttal, we contend that the activists did not bring those people there. People came by virtue of their own autonomy, rather than out of some paternalistic notion of “blind self-harm.” The crowd acted knowing full well the consequences of their actions; one does not jump in front of a police cruiser without understanding that the police may retaliate violently, particularly after the cops had tazed somebody immediately prior. Moreover, the police were not in a position to kettle anyone; in fact, they did not manage (or even attempt) to make a single arrest. In short, the crowd had won. And yet the activists—demonstrating little to no tactical awareness or understanding of the stakes of abolitionist struggle—adopted a defensive posture.

Instead of building upon the defeat of LPD and using it to gain momentum against both the police and the fraternity, however, the activists re-pacified the crowd, stripping people of their autonomy and reimposing the bureaucratic frustration of emails and petitions. The night ended with the activists leading the protestors back to campus via the sidewalk and telling everyone to go home.

Again commenting on the eruption of the George Floyd Rebellion, Shemon and Arturo write: “Hearing the battle cry of Black Lives Matter, a significant number of poor and working class whites joined the rebellions,” and “[t]here is nothing more dangerous to the American bourgeoisie than a multi-racial class struggle.” When people take the streets together, really take the streets, the ruling class feels threatened. As such, it cannot be allowed to occur. And, as such, a diffuse array of systems of cultural and physical repression come into play, one of which is middle-class activism and its hollowing effect on revolt.

In further pursuit of demonstrating the emptiness of middle-class activism as compared to multi-racial struggle, we raise two contrasting examples of what it means to “take the streets,” as they played out during the anti-FIJI movement. One version consists of pre-approved, police-escorted demonstrations on the empty streets of a university campus. The latter is a busy downtown intersection on a Friday night, police cruisers hemmed in by a multi-racial, multi-class crowd in direct confrontation with the flows of capital and police brutality. Though they bear the same name, these are two very different modes of action. One creates leverage against those in power, and the other is cultivated by that same powerful class. Here, we also want to point out a clear demarcation in terms of who tends to pursue direct action as a first line of defense: working-class black folks were the first to take the streets, encouraging others to follow suit. Conversely, the self-styled Black Leader who has repeatedly demonstrated petty bourgeois allegiances sought to cut off direct action. Truly, as Idris Robinson writes: “The so-called the Black leadership, therefore, cannot and does not exist. It is a chimera to be found exclusively in the white liberal imagination.” The Black Leaders Movement of Lincoln, Nebraska, and its representatives lead people only to surrender and defeat.

The now-repeated downward trajectory of Lincoln protests demonstrates a curious directionality in relation to the local Summer 2020 uprisings. As we wrote previously, this same activist clique, centered around Lincoln BLM, disarticulated the summer uprising by similar means. In both the George Floyd Rebellion and the anti-FIJI movement, a diverse, spontaneous coalition that crossed identitarian and tactical boundaries emerged. This coalition was then ideologically divided by activist cliques deploying middle-class prohibitions against protestors, while those activists act in visible concert with the police. In both movements, an ungovernable revolutionary potential was stymied and prevented from elaborating itself. This constitutes a repeated interruption of revolutionary potential, which denies the crowd the opportunity to experiment with a true diversity of tactics and articulate its own ideas of what should be done and how. This disruption of the revolutionary trajectory repeatedly leads to the death of any nascent movements with which these activists come into contact. The next uprising is eternally doomed to build momentum once again, from scratch, never having any solid ground on which to stand due to the incessant megaphonic distractions of the activists.

Rather than the activists’ self-serving claim that they are trying to “give voice to people’s anger,” a close study of their actions and the subsequent effects reveals that they are, in fact, the extinguishers of revolution.

Conclusion

Whereas the activists continually bemoan the chronic dissolution of protests in Lincoln, we propose that they are participating in a counterinsurgent interruption of revolutionary potential by forcing movements to enter into conversation with hegemonic institutions. These entities deploy time-tested strategies of attrition (meetings, petitions, committees, listening sessions) which translate fury into disillusionment. Thus, the local contingent of middle-class activists is a key component of Lincoln’s counterinsurgency: the police defend activists’ positions so long as the activists siphon insurrectionary potential into the bureaucratic labyrinths over which the activists hope to preside. It is no surprise, then, that the activists are always keen on meeting with mayors, senators, and chancellors; it is no surprise that they are the executives of their own nonprofits and members of Greek life: their careerist aspirations align them with the existing power structures, and they are loathe to tolerate any attack upon their professional development.

So long as middle-class activism holds the reins of protest in Lincoln, there is no hope for liberation from sexual, police, and other forms of violence. So long as the activists’ professional aspirations are heeded as the beacon which will lead people to freedom, people will instead be continually led to graveyards of possibility.

For those who wish for more than an endless cycle of outrage that only begets further outrage as the institutions (which are designed to deny change) deny change, it is imperative to experiment with strategies for breaking free from this counterinsurgent hegemony. As the Invisible Committee writes, “There’s no ideal form of action. What’s essential is that action assume a certain form, that it give rise to a form instead of having one imposed on” (60). We suggest that readers of this piece look into the essays we have referenced here as well as the broader body of work available through such outlets as Ill Will Editions and It’s Going Down News.

Struggles in Lincoln are linked with a fabric of resistance that spans the globe. People in Lincoln must study what is going on elsewhere and apply what they learn locally. Without this, local movements are doomed to fall prey to ever-evolving strategies of counterinsurgency; and concerned individuals will be thus consigned to do something in the halls of power, though it is never quite clear what.

The momentary overlap between disparate struggles in Lincoln provided a brief potential avenue for the convergence of cross-class and cross-racial solidarity as seen in this case of white, petty bourgouis protestors willing to fight the police in support of black proletarian protestors. This potentiality is ultimate destroyed by the petty bourgouis willingness to submit to middle-class activist leadership. Rather than walk into such traps, we emphasize that those in power are studying how to quell unrest and are using well-intentioned organizers to do so. Those in Lincoln and around the world who feel restless must study how to resist and build power in response.